One of the “World’s Dudes” series of cigarette cards from Allen & Ginter, late 1800s: “British Diplomat.” So glad that I don’t have to dress like this.

As I wrote in my last post, foreign service officers are required to achieve professional working proficiency in the language that we’re studying. Officially, the Foreign Service Institute uses the Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) scale to assess language proficiency. In my professional opinion, the testing unit at FSI does a pretty good job of adhering to the standards for proficiency. And in my experience as a language learner, FSI language departments do a pretty good job of preparing us to be assessed by the ILR standards.

But the situation more nuanced than you’d think.

I’ve had this conversation with many of my classmates over the last several months, as we’ve struggled with the task of language learning. We all have the sense that something’s not completely right with the language curriculum. The problem came into focus for me when we went on the language immersion trip in March.

I also saw symptoms of this problem in some colleagues who I served with in China. Being married to a native speaker of Chinese, I have plenty of opportunity to practice daily life language. But my colleagues who only learned Chinese in the classroom had a different experience. They had good work-related language skills, but their skill in talking about daily life, using language that local people used, was weaker. Several people joked that they could negotiate a trade treaty in Chinese, but they couldn’t order a pizza. Language for daily life doesn’t seem to be a high priority for the language programs at FSI. And although it can be frustrating for us once we land in country, it isn’t hard to understand why the language programs do it that way.

Generally speaking, we can think about the goals of language learning in different ways. On the one hand, we needs to be able to navigate daily life: ask for the bathroom, or talk about the weather. Answering the telephone has got to be the hardest everyday task in a foreign language. Every language learner is afraid of a ringing telephone. Don’t take my word for it, ask any language learner how stressful it is to talk on the telephone in a foreign language. This kind of language use is the highest-frequency language use. It’s how people use language on a day-to-day basis. However, this is de-emphasized at FSI. It seems that there is a deliberate choice not to focus on that. Why? Keep reading.

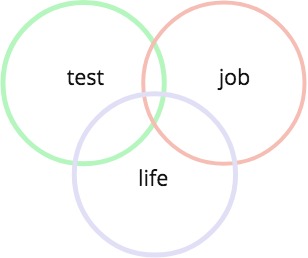

Another kind of language is professional use. This is the language that we use in the office: when we are interacting with our locally-engaged staff (LES), when we interview visa applicants, when we meet with local government officials and businesspeople. The language is pretty predictable and structured, and it’s at a more formal register. More importantly, this kind of language contains words and structures that are very different from daily life language. Although language for daily life and professional use is the same language, the functions are very different. And significantly for a language program, if you have to teach both daily-life language and formal job-related language, then you have to teach two different units. If you could encapsulate the language functions into zones, it might look something like this:

Areas of focus when I’m learning a language.

There’s another area of focus in that chart, which I’ll come back to later.

If you run a language program, and your instructional time is limited (whose time isn’t limited? Mine sure is!), then you have to prioritize.

If you have to prioritize between teaching daily-life language and work-related language, which should you teach?

I look at the question of priorities in two ways. First is the perspective of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

The (in)famous hierarchy of needs

The most basic level is physiological. A person needs to eat. Â If you want a person to be able to live in foreign country, that person needs to be able to get around in society. From that perspective, it makes sense to focus on daily life language, right?

But there’s another way to look at the problem. Let’s look at it from the perspective of why we are sending diplomats abroad in the first place. Although it will be a struggle to get around in daily life without great skills in basic language use, the real reason that we’re sent abroad is to conduct foreign affairs. Our personal comfort and convenience should take a back seat to our job performance. From that perspective, we should focus on work-related language. It’s much more important for the U.S. government that we are able to talk about banking regulations or the humane treatment of prisoners, than it is to be able to pick up our dry-cleaning, for example.

But even that isn’t the end of the debate. We can’t ignore another, competing force. The third area of the chart above is the “Language that I need to pass the test.” The only way that our language skill will be formally assessed is during the End of Training (EOT) test. The stakes are very high for that test. There are consequences for testing well or poorly. So as a language student, it makes a lot of sense, even though it’s more than a little mercenary, for me to focus on what I have to do in order to score well on the test.

Of course, in an ideal world, there would be enormous overlap between these three areas. I’d love to draw a chart like this:

An ideal Venn diagram of the three competing priorities.

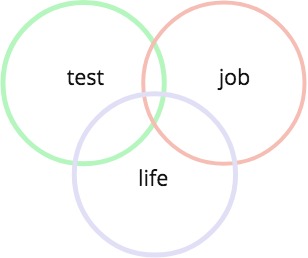

However, it often seems that the situation should be charted more like this:

Reality sucks

In my language program, the instructors are very cognizant of the competing priorities. I often fear that they feel that they are caught in the middle of this struggle. They want to help us met our goals, but sometimes our mercenary mindset clashes with their ideals of teaching us the language with a well-rounded approach.

In an ideal world, language learners would focus  solely on their work-related needs, so that they can succeed in their job after they arrive at post. They would hope that they could get around with the language in daily life, and ignore the test. A test score is just a number. It’s more important that they actually are able to do their job. Right? Well,…

These are the competing forces that we interact with during language training. Like I wrote above, it’s more nuanced than a simple test score. There is a lot of room for interpretation in a statement of proficiency like: “Can typically discuss particular interests and special fields of competence with reasonable ease.”

Life is messy. Definitions are fuzzy, and clear-cut examples are hard to find. Language learning as a professional task is complex and hard to predict. Like the car commercials used to say: “Your mileage may vary.”