There’s a Nation-Wide Shortage of Sleeping Bags

“Everybody out, now, go!”

My supervisor waved everyone toward the exits, as he rushed around the office, locking all the doors and securing all of our materials. I grabbed all of my stuff, made sure that I had my mask on, checked that everyone on my team got the message to leave, and rushed out of the building. People from other offices in the building were also scrambling to get out as fast as they could. No one was panicking, everyone was calm, but they all showed the same urgency to get out of the building. No one wanted to get stuck inside.

A few years ago, I took the special training course that the State Department requires for all diplomats posted overseas. The official name is “Foreign Affairs Counter Terrorism,” or FACT. We call it “crash-bang.” It’s a week-long course held at a military base, and it prepares us for when things go horribly wrong while posted overseas. Among the modules are defensive driving. We got to crash cars into other cars. It was incredibly fun. The first aid section was stomach-turning for several people. Can you say “sucking chest wound?” We even got to practice crawling through a smoke-filled room, and climbing into a helicopter while wearing flack jackets and helmets. The training is serious and important; I know that people have saved their lives and others’ at post when things went south.

Stubbornly adhering to its zero-tolerance COVID-19 policy, the Chinese government is struggling to control the latest outbreak. The omicron variant has come to China, and just like in the rest of the world, its high infectious rate is causing outbreaks throughout the country. The absolute numbers are small. While the United States saw daily cases numbers in the hundreds of thousands, this week the new daily numbers are in the low thousands. But when your goal is zero, any new case is unacceptable. And there are consequences of this hard line. Local officials have lost their jobs because of their inability to control the spread of the virus. The local health authorities have seemingly absolute authority to control people’s movements and to implement lockdowns and mandate mass testing. All of which we are seeing in China this month.

I don’t know exactly what’s happening in Shanghai now. There isn’t a lot of objective, clear news. And the policy seems to be shifting. In recent weeks, we saw several cases of businesses being locked down, and anyone who happened to be inside when that happened had to get comfortable. They were stuck there for 48 hours while they were tested twice before being released (if their tests were negative, of course). This has happened to people that I work with. The father of one of my coworkers was identified as a “close contact” of a confirmed case. That meant that he was carted off to a quarantine facility, which in this case was a hotel room. He’s confined there for 14 days, while getting tested twice a day, every day.

There is a silver lining to the increasing numbers of COVID-19 infections in China, though. Just like in the rest of the world, although omicron is more contagious, it’s much, much less severe. Although infections are up in China, deaths aren’t. And the vast majority of confirmed infections are asymptomatic. COVID-19 simply isn’t having a large impact on people’s health.

People aren’t afraid of getting sick anymore, which is good. But they are afraid of getting caught up in the government’s unrelenting zero-tolerance measures, which have not yet changed. And the current approach has an enormous impact on people’s lives.

The reason that my supervisor rushed everyone out of the office was because he got word that our building was going into lockdown. This is happening all over the city. Once a building is locked down, no one can leave until the health authorities say so. One of my coworkers was called home in the middle of the day last week, because someone who lives in her apartment building was a close contact of a close contact. Once she returned home, she couldn’t leave her apartment for three days. She had to have two negative tests before she could return to work. Another coworker received the same notification. She has already been tested four times, and she still hasn’t been given the green light to leave her apartment. Today is day seven for her.

The reason everyone was eager to leave the building was that no one wanted to be locked down. Getting locked down anywhere is bad, but being locked down in the office is much worse than being locked down in your own house.

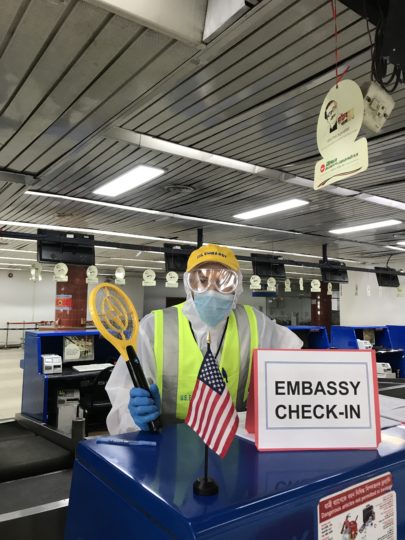

Back in normal times, pre-COVID, we were encouraged to prepare a “Go Bag” in our house. In the case of a sudden emergency, if we had to leave in a hurry, we should have a bag with a change of clothes, our passports and important documents, etc. If we were being evacuated, we could grab the bag on our way to the airport. Now, we are told to have a “Stay Bag” in the office, with a change of clothes and other necessities. Last week I bought a sleeping bag to keep in my office. I wasn’t the only person with that great idea, and I know that, because now there’s a nation-wide shortage of sleeping bags.

Sure enough, the building where I work is now in lockdown, so I can’t go to work today. Yesterday, we heard another rumor that my apartment building would be locked down today. We haven’t heard anything yet, though. In theory, we can go outside and walk around. But no one wants to enter a store, because once you’re inside somewhere, there’s a chance that you could be locked in.

China is experiencing a strong case of deja vu. Is it 2022, or 2020, too?