I moved this blog

I’m on Substack now

Still free and everything, but Substack is a little easier for me.

I’m on Substack now

Still free and everything, but Substack is a little easier for me.

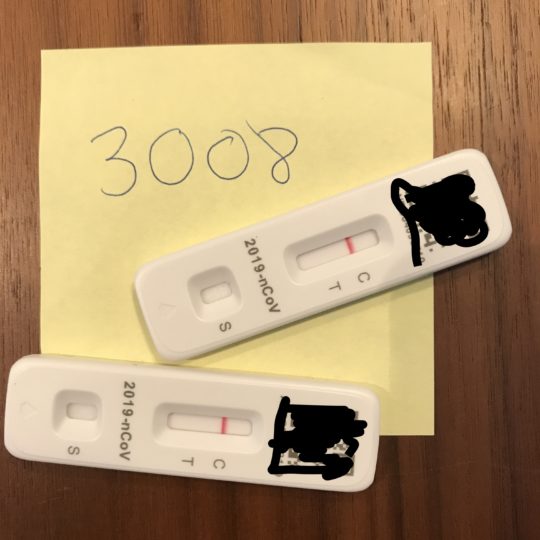

Today is Day 13 of a 4-day lockdown. The lockdown has limited the availability of food and access to quality health care. We’re fine for now, but the situation is unstable, changing every day.

A few days ago, the Department decided to put the Consulate on “Ordered Departure.” When a post goes on Ordered Departure, American personnel who aren’t performing a “mission-critical” function, especially those with families with small children, must leave. They have to return to DC, and work remotely (as best they can) from (cramped and crappy) hotel rooms until this is over.

We lived through this two years ago in Dhaka. We had the choice to leave then, and we chose to stay. We felt less vulnerable, and more importantly, we felt that we could help. Looking back, I feel that we made the right decision. We did some amazing work then; we really helped a lot of people. I feel the same way this time. Our core mission in Embassies and Consulates is to help American Citizens who are in need.

Ordinarily, my position here in Shanghai is not considered to be mission-critical. Cultural programming is the last thing on anyone’s mind when the city is shut down and under a cloud of uncertainty. Under Ordered Departure, I would be ordered to leave.

We did a lot of thinking about the situation, and decided that it made more sense for us to try to stay. We can be useful here. My wife already works in the Consular section. Several months ago, before any of this started, I asked for and received authorization to perform consular functions in Shanghai, everything from notarial services to adjudicating visas to American Citizen Services. At the time, I thought maybe I could help during the summer visa rush, when tens of thousands of students apply for visas to study in the United States. I told post leadership that we would like to stay and help, if they need two extra pairs of hands. As it happens, so many officers in the Consular section must leave, that they’re short-handed.

Consulate leadership accepted our offer to stay and help. So instead of evacuating to “safe haven” in the United States, I will be detailed to the Consular section, for as long as Ordered Departure lasts (anywhere from a few weeks to a few months).

We are aware of the potential dangers that we face by staying, but I’m not convinced that it’s as dangerous for us as it might be for others. We are physically safe. Violent crime is extremely rare, even crime of opportunity is low. The national surveillance system in China is like something in a George Orwell novel. It’s pretty hard to get away with crime here.

We do face two real threats by staying, though: food and medical care. Because the city is locked down, we can’t go to the grocery store. We are in a better , though, because we speak Chinese. My wife is on the cell phone all day, monitoring “group buys” of food. Unlike some other people, we have plenty of food. The food threat isn’t as serious for us (at least, not yet). Our food situation is much, much better than many people in the city.

Medical care is a larger problem. Hospitals are reluctant to admit anyone, for fear of spreading the virus. There are real stories of patients being refused service because they were running a low-grade fever, which of course is one of the symptoms of COVID. If we have a serious medical issue, it will be harder to get treatment. Harder, but not impossible. A guy in our building cut himself badly a few days ago while chopping vegetables in his kitchen. The building management managed to get him to a hospital and he got stitched up. There were some delays, but not too much.

The city-wide lockdown continues, we haven’t been out of our apartment since April 1, except for three short trips out to a central testing site nearby. We don’t know when we will be able to leave. For now, “helping” means reading my work emails and waiting to be called. I think the Consular section will get more busy later on. After the lockdown is over, it will take some time for the officers to return to post. In that time window, the section will need our help to perform routine Consular services.

We’re fine for now. We are practicing what the Department calls “situational awareness.” We’ve been through this before, and this time we have the advantage of no language barrier. We’re in good health, and unlike last time, we’re triple-vaccinated. I think this will end much sooner than the Department predicts. I could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure that I’m right. In the meantime, there are some frightened Americans in Shanghai who don’t have the same support network and diplomatic immunity that I have. We can help these folks, this is what I signed up for, this is what I want to be doing.

It’s also something that I didn’t expect to see in China, least of all in Shanghai.

Today is day seven of a four-day lockdown, and no end is in sight.

I wasn’t surprised that the lockdown didn’t end on schedule. No one I know was surprised. This is Omicron, and we saw what it did to the rest of the world. We knew it would come to China, and we knew that it would be this hard to control. The number of new infections is still rising, and the official narrative is still couching the situation as a “war.” And wars must be won. They can’t be lost. For Shanghai, that means continued lockdown, continued testing (we have tested four times already), and waiting for the numbers to go down.

When you can’t go outside your apartment, you can’t buy groceries. We are fine, we have plenty of food. We were advised to store enough food to last up to two weeks. We are two adults with no dietary restrictions and with relatively easygoing palettes. For us, the only challenge is finding storage space in a very small apartment with a very, very small refrigerator.

And it’s a good thing that we stored up food, because buying food has now become a problem.

China’s food-delivery system is world-class. I’ve never experienced a better delivery system than in China. We usually buy produce and meat online, using a grocery delivery service. In normal times, you see delivery guys (it’s usually males) everywhere, scooting around on their little electric motorcycles, delivering packages, meals, and food. Ordering groceries online is actually more efficient than going to the store ourselves; we could place an order on our cellphone app, and the stuff could be delivered in 15-20 minutes.

But when you lock down the city, and don’t let anyone out of their house, then stores can’t open, and delivery guys can’t make deliveries. The city government issued special passes to delivery guys. But most of the delivery guys can’t work because if they’re locked down for other reasons. The efficient system of food-on-demand is broken. The food supply, usually ample and varied, contracted.

We’re fine, we aren’t starving. We have plenty of food. But not everyone is as lucky as we are. Some people are struggling to get enough food.

The online ordering apps are still working, but the inventory is updated in real time. When things are sold out, they online store shows that the item is no longer available. The stores “open” online at a fixed time, and there is a small window of time when you can place orders before everything is gone. The stores start taking online orders at 6:00 AM. The other day we woke up at 5:45 AM to fill our carts. I was using the app for one store, my wife was using the app for another store. We figured if both of us try at the same time, maybe one of us will be able to get something.

We kept getting the “busy” notification on the apps when we were trying to add items, and when we tried to place the order. There are at least 24 million people in Shanghai, and they are all in the same situation as us. I don’t know if all 24 million were on the same app as I was, but it felt like it. The app didn’t crash (not too often, anyway), but it displayed a “busy” notification as other people who were faster than I was grabbed the food. As I refreshed the app, the inventory was updated. I kept getting notified that this or that product was sold out.

Eventually, the app told me that their delivery schedule was filled. I would get no food deliveries that day. The window would open up at 6:00 tomorrow; I’d have to try again then.

Socialism came to the rescue. The city government started distributing food packages to residents. There were reports of quality issues with some of the food, but overall it’s been a big help. We refused the first round of food, because we felt we had enough. Yesterday we accepted a package, though. Our apartment building also organized a group buy of meat and fruit.

It seems to be working, but people are getting worried. There are many different opinions about the government’s decisions, many of which are critical. The government is working hard to maintain their iron-fisted pandemic control protocol, and also to keep people fed. I’m hearing a lot of doubts expressed about the government’s ability to do those things. I am glad this is not my problem to fix. I don’t know that I agree with the direction that the government has decided to take, but I do know that if I were suddenly placed in charge, I would have no idea what to do.

Tensions are high among the local people. The original plan was to end this lockdown after eight days. We could plan for that, and count down the days to the end. Facing an indefinite lockdown with no idea when it will end takes away people’s hope. Now the city is back to where it was two years ago, when this drama started.

In the State Department’s counter-threat training, I learned that when people are afraid, their IQ drops ten points. I believe that. I’ve seen people make bad decisions and do stupid things when they are afraid. And people here in Shanghai are afraid now. Yesterday I saw a statistic that one-third of Shanghai residents live paycheck-to-paycheck. When people can’t go to work, they have no money. People are afraid of losing their livelihoods. Not being able to get fresh food is adding to the stress.

When the number of daily cases in the United States continues to hover around 27,000, the number 52 seems meaninglessly small. It’s a rounding error, not even worth thinking about. But if your goal is zero, then 52 is a very large number. It’s a very large problem.

China is persistently sticking to its policy of completely eradicating the COVID virus. Their goal is zero cases. In Chinese, there is a new meaning of the word “reset” 清零. The original meaning, returning a computer to factory settings, now means that an area has been completely cleansed of COVID cases. If you had cases in your neighborhood, but through quarantine and isolation, you no longer have cases, then your area has been “reset.” Although they’ve since refined the term to match their more targeted, granular approach, the ultimate goal has not changed: China will completely eradicate the COVID virus from every corner of the country.

To people with the attitude that the only option is complete and total “victory,” the west’s co-existence strategy looks like giving up. The United States and other western countries have lost their resolve, and have callously decided that the lives of thousands of people is a price worth paying in order to preserve the economy. In contrast, the Chinese government insists that they will not surrender, vowing to continue fighting until they achieve complete victory. Failure is not an option, and everyone is expected to get in line and join in the fight. Alternative approaches are not only unwelcome, but voicing them can lead to censure or worse.

If the military metaphor is obvious to you, it’s because that is the tone that the authorities continually take. Couching social programs in military terms is commonplace here, and the pandemic The Chinese term for “counter-pandemic” is a homonym for “war of resistance” in Chinese.

The “reset” approach actually worked pretty well to control the virus two years ago. COVID version 1.0 wasn’t as contagious. Early detection and isolation were effective in stopping the spread.

Then the variants arrived. The U.S. and other countries were ravaged by the Omicron variant several months ago, and now Omicron has finally arrived in China. The virus changed. The Chinese government’s posture hasn’t.

Several cities, and one entire province, were “locked down” for weeks starting in late 2021, when the virus started getting out of control. Again, the numbers were relatively low, especially when compared to the experience of the United States. We wouldn’t blink if the state of Indiana had 1,500 new cases in one day. But numbers like that were large enough for the Chinese government to take drastic action.

And when the numbers in Shanghai started growing, the rumors grew as well. The city government insisted that they had it under control, they didn’t need to shut down the city. I think people wanted to believe that, but couldn’t.

Cases continued to grow, and people got more and more nervous. Last week, as we were going to work in the morning, the subway station was eerily quiet. People weren’t taking the subway for fear of getting tagged as a “close contact” and hauled off to a quarantine center.

Panic buying of food (not toilet paper). We had been advised a long time ago to have two weeks’ worth of food on-hand, so our pantry was pretty well stocked.

Still, the government denied that a lockdown was coming. The narrative was that the city, as the financial heart center of the country, the most modern city in China, the “magic city” was somehow different. To use a term from a decade ago, Shanghai was too big to fail.

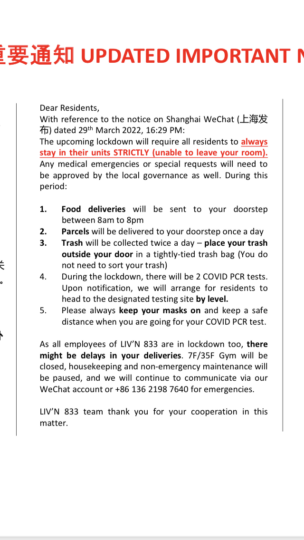

The day after this story came out, we had this announcement. Shanghai would lock down in two steps.

Not an April Fool’s joke, our lockdown started on Friday the 1st. Our apartment building told us that we were confined to our apartments. And that’s where we are now. We can only leave the apartment when we are shepherded to the testing centers.

We were herded to the testing center on Friday morning.

Everyone has to register their cell phones with the government. All of our health information is in the cloud, and must be presented on-demand, usually when we enter office buildings and shopping centers.

In theory, the lockdown of this half of the city will last for four days, until April 5. I suspect that few people believe that. The other half of the city, which began lockdown last week, was scheduled to be opened back up two hours after our lockdown began. It is still locked down.

So, we wait. We have plenty of food. Our pantry is well-stocked, but our refrigerator is pretty small. We’re storing some vegetables in a bathroom sink.

While we are locked down, we can’t go to the office. We can’t hold our programs. We can’t with our counterparts in the local government. No one can say how long this will last. I’m not diplomatting, and I hate that.

“Everybody out, now, go!”

My supervisor waved everyone toward the exits, as he rushed around the office, locking all the doors and securing all of our materials. I grabbed all of my stuff, made sure that I had my mask on, checked that everyone on my team got the message to leave, and rushed out of the building. People from other offices in the building were also scrambling to get out as fast as they could. No one was panicking, everyone was calm, but they all showed the same urgency to get out of the building. No one wanted to get stuck inside.

A few years ago, I took the special training course that the State Department requires for all diplomats posted overseas. The official name is “Foreign Affairs Counter Terrorism,” or FACT. We call it “crash-bang.” It’s a week-long course held at a military base, and it prepares us for when things go horribly wrong while posted overseas. Among the modules are defensive driving. We got to crash cars into other cars. It was incredibly fun. The first aid section was stomach-turning for several people. Can you say “sucking chest wound?” We even got to practice crawling through a smoke-filled room, and climbing into a helicopter while wearing flack jackets and helmets. The training is serious and important; I know that people have saved their lives and others’ at post when things went south.

Stubbornly adhering to its zero-tolerance COVID-19 policy, the Chinese government is struggling to control the latest outbreak. The omicron variant has come to China, and just like in the rest of the world, its high infectious rate is causing outbreaks throughout the country. The absolute numbers are small. While the United States saw daily cases numbers in the hundreds of thousands, this week the new daily numbers are in the low thousands. But when your goal is zero, any new case is unacceptable. And there are consequences of this hard line. Local officials have lost their jobs because of their inability to control the spread of the virus. The local health authorities have seemingly absolute authority to control people’s movements and to implement lockdowns and mandate mass testing. All of which we are seeing in China this month.

I don’t know exactly what’s happening in Shanghai now. There isn’t a lot of objective, clear news. And the policy seems to be shifting. In recent weeks, we saw several cases of businesses being locked down, and anyone who happened to be inside when that happened had to get comfortable. They were stuck there for 48 hours while they were tested twice before being released (if their tests were negative, of course). This has happened to people that I work with. The father of one of my coworkers was identified as a “close contact” of a confirmed case. That meant that he was carted off to a quarantine facility, which in this case was a hotel room. He’s confined there for 14 days, while getting tested twice a day, every day.

There is a silver lining to the increasing numbers of COVID-19 infections in China, though. Just like in the rest of the world, although omicron is more contagious, it’s much, much less severe. Although infections are up in China, deaths aren’t. And the vast majority of confirmed infections are asymptomatic. COVID-19 simply isn’t having a large impact on people’s health.

People aren’t afraid of getting sick anymore, which is good. But they are afraid of getting caught up in the government’s unrelenting zero-tolerance measures, which have not yet changed. And the current approach has an enormous impact on people’s lives.

The reason that my supervisor rushed everyone out of the office was because he got word that our building was going into lockdown. This is happening all over the city. Once a building is locked down, no one can leave until the health authorities say so. One of my coworkers was called home in the middle of the day last week, because someone who lives in her apartment building was a close contact of a close contact. Once she returned home, she couldn’t leave her apartment for three days. She had to have two negative tests before she could return to work. Another coworker received the same notification. She has already been tested four times, and she still hasn’t been given the green light to leave her apartment. Today is day seven for her.

The reason everyone was eager to leave the building was that no one wanted to be locked down. Getting locked down anywhere is bad, but being locked down in the office is much worse than being locked down in your own house.

Back in normal times, pre-COVID, we were encouraged to prepare a “Go Bag” in our house. In the case of a sudden emergency, if we had to leave in a hurry, we should have a bag with a change of clothes, our passports and important documents, etc. If we were being evacuated, we could grab the bag on our way to the airport. Now, we are told to have a “Stay Bag” in the office, with a change of clothes and other necessities. Last week I bought a sleeping bag to keep in my office. I wasn’t the only person with that great idea, and I know that, because now there’s a nation-wide shortage of sleeping bags.

Sure enough, the building where I work is now in lockdown, so I can’t go to work today. Yesterday, we heard another rumor that my apartment building would be locked down today. We haven’t heard anything yet, though. In theory, we can go outside and walk around. But no one wants to enter a store, because once you’re inside somewhere, there’s a chance that you could be locked in.

China is experiencing a strong case of deja vu. Is it 2022, or 2020, too?

I received an email from the Foreign Service Institute’s language testing unit. They did a routine review of my recent language test, and adjusted my score up. My speaking score is now a solid 4, up from 3+. That means a little more language incentive pay, but more importantly, that means that I’m on the right track to improve my language skills.

I’ll still test again in six months, to try to improve my reading score. I’m confident that I can do it.

The local government has adopted a “zero tolerance” policy regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. They’re convinced that their approach to controlling the spread of the virus has been proven correct. They point to the very low numbers of infections in China. They consider that to validate their strict social control measures. In contrast, they point to what they consider to be an out-of-control situation in the West.

It’s impossible to ignore the wide difference in transmission numbers that result from China’s approach. There is no doubt that China is controlling the spread of the virus much more successfully than other countries are.

Everything comes at a cost, of course, and China’s success in controlling the pandemic is no exception. The cost is borne by the local people. They have to deal with limitations and restrictions that disrupt their lives, in little and not-so-little ways.

A coworker told me yesterday that the city has cancelled all large, in-person events through the end of the year. All concerts, parties, exhibitions, graduation ceremonies, celebrations, have been moved to online and virtual formats. Many schools are back to holding classes online, too.

Travel has also taken a hit. When people travel, the virus travels, too. We’ve had to cancel many official trips within the country. We can take personal trips, but there’s a huge risk. If you travel outside the city, and an outbreak is discovered (“outbreak” in China means the number of confirmed cases is more than zero), the place where you are traveling to could be locked down. Your long weekend trip could be extended by 14 days, locked inside a crummy quarantine hotel. Which you have to pay for.

Although we really wanted to do more in-country travel, the risks are too high. We aren’t worried about getting sick: we’re triple-vaccinated. But in China, when an area gets locked down, no one gets in or out, regardless of vaccination status, nationality, or color of your passport. The danger of getting sick is pretty small, but the risk of massive inconvenience and disruption to our lives is quite high.

Luckily for us, we’re in Shanghai, where there’s a lot to do, see, eat, hear, experience. There is no danger of getting bored in Shanghai. The staycations that we are planning are pretty great. But the psychological effect of knowing that we have to stay in the city deducts some of the fun. Although it isn’t a bad thing, we’re stuck here.

It was 11:10 pm. I was worn out. I had been “on” for more than 2 1/2 hours. I felt drained. They say that the language test isn’t supposed to feel fun. In fact, you’re supposed to feel stressed. The examiners are supposed to push you. They did their job. My brain was as tired as my body.

My language score had expired ten days before I got to post. No valid language score means no language incentive pay, which is a difference of hundreds of dollars a month. Testing again to re-establish language proficiency isn’t just a matter of personal pride, there’s a financial incentive as well.

When you’re in DC for training, you can test at the testing center in the Foreign Service Institute. The tester and examiner are both in the room with you, you can interact with them naturally during the test, it’s more like a real interaction. When you test from post, you have to do it via Digital Video Conferencing. That used to be a significant thing back in the pre-plague years. It used to feel strange having a meeting over videoconference. Now, of course, we’re all used to interacting on Zoom, WebEx, Teams, Skype, FaceTime, etc.

At 7:30 am Monday morning Washington, D.C. time, I signed in to WebEx for my language test. That’s 8:30 pm China time. After a full day of work. The test finished after 11:00 pm.

This was my fifth Foreign Service language test, and the second time testing remotely from post. It was also my third Chinese language test. I tested in Vietnamese after my language training was done and I was ready to go to post. Then I tried again after almost two years of in-country work, during which time I studied with a private tutor four hours a week. Both times, I hit a wall. I improved, but not enough.

I’m clearly doing something wrong. I’m not making the progress that I want to. The last two times I tested in Chinese, I “only” got to a 3+/3+. This was the same score that I got in 2016, after two years in China. I put “only” in quotes, because a 3+/3+ is objectively a good score. I know many people who struggle to get to a 3/3. The “+” after the number means that my performance was somewhere between a 3 and a 4. The testers witnessed me wandering into the range of a 4 at times, but not consistently. So for me, the 4 isn’t an impossible goal. But exactly what am I doing wrong?

As someone who’s been a speaker of Chinese for 30+ years, and who’s put in a lot of hours of study, I was really hoping to break through to a 4. The highest score is a 5, which equates to the language ability of a college-educated native speaker. The folks in the Foreign Service Institute call that a “unicorn,” almost no one ever gets to a 5 in a language that isn’t their native tongue. But I know people who have achieved a 4 in Chinese. Why can’t I?

I have such mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, the external validation of getting to a 4 isn’t my main goal. They say that you are only really competing with yourself. As long as you can look back and see that your current performance is better than your past performance, you’re doing well. From that point of view, I’m making progress. I feel that my Chinese is getting better and better. But the external validation isn’t nothing, either.

One of my friends, a native speaker of Chinese, tested in Chinese (I’m still not sure why she did it, but whatever), and tested at the same level that I did. If my score is the same as that of a native speaker, then clearly what’s wrong isn’t my raw language ability. It must be my test-taking strategy.

Time to take stock, and re-examine how I’m preparing for the test. This isn’t over. I can test every six months. I still have more than 19 months left in this tour. There are still three more shots at the brass ring. And I’m going to take every single one of those opportunities to show myself that I can do it.

Foreign Service officers have different “portfolios†during specific tours. During my last tour of duty in Bangladesh, I was a visa chief, so most of the time, I was in the office. The few conversations that I had outside the office were about visa policies.

This time around, though, I have a more public-facing position in China. I meet with people outside the office several times a week. Which is great, because I get to diplomat in Chinese. My job during this tour requires me (among other things) to promote education in the United States to Chinese students. This week I went on a road trip to four cities in our consular district. We partnered with several U.S. universities, and set up information booths at our education fair.

A mix of parents and students come to our booths to ask about studying in the United States. I haven’t felt this useful in a long time. In Bangladesh, I didn’t have any of the local language, so I was limited to talking with people who already spoke English. I could muddle by in Vietnamese when I was in Vietnam, but I never felt as comfortable with Vietnamese as I do in Chinese.

With my background in academia, experience as a parent of college students, and pretty good Chinese, I felt useful. I felt like I really communicated with anxious parents and curious students, and connected with people this week.

The week was capped off by an education fair back in Shanghai. At our booth in the exhibition hall, I spent the day talking, dispelling myths, and clearing up some misunderstandings. I hope that straight answers from an American officer, delivered directly in Chinese, was convincing enough to the people I talked with.

My big takeaway from this week is that although there is still strong interest in studying in the United States, there is a real dearth of information about how to do it right. My team and I are already brainstorming ideas to overcome this information gap, such as online seminars for parents. We have a lot of work to do, and our resources are limited. But I love to connect with people, and I believe strongly in the value of an American education.

After the longest home leave ever, I finally got to post. But then I had to sit in a hotel room for two weeks for the mandated quarantine period. Then a few days after we got out of quarantine, there was a week-long national holiday. I was itching to get to work and start to earn my paycheck!

My job during this tour is to lead the public engagement for the Consulate. This “consular district” (the area of China that we interface with) has over 200 million people. That’s a lot of public to engage with.

Last week I visited the city of Ningbo 寧波, which is in our consular district, but is two hours away from Shanghai by high-speed train.

Shanghai train stations are big, modern, and clean, but just as crowded as any other train station that I’ve been to in China.

Travel in China is back to routine, but there’s always a risk of getting “caught out.” The pandemic is still ongoing, and the Chinese government is sticking to the “zero-tolerance” control mechanism. If there’s a local outbreak, the locality is shut down, and no one gets in our out. Diplomatic immunity doesn’t apply! I had to update the social tracking application on my phone to include the city of Ningbo. In the train station someone took my temperature at least three times. Luckily I haven’t heard from the local health authorities that I was exposed to COVID-19. Knock on wood.

I can confirm that the countryside in my consular district is stunningly beautiful.

In Ningo, I got to visit two art museums, one public and one private.

I also visited a special-education school that we are working with. One of the teachers is actually a parent of a student at the school. Her child has Down’s Syndrome. She told me that she quit her job to start working at the school, so that she could know how to best help her son maximize his potential. Her story was moving. Like many parents of special-needs children, she struggles to acceptance for her son, not only in general society, but from even her own extended family. Her love and dedication to her child were obvious. I confess that I choked up at one point.

It was a long day: I left the house at 6:30am, and didn’t get home until almost 8:00pm. But it was a great trip. I think we will be able to expand our engagement, and to promote American values. For me personally, I felt like I was doing real people-to-people diplomacy for the first time in a long time. I speak pretty good Chinese, so I can really connect with people. As long as we keep talking with each other, we can narrow gaps in understanding. That’s the idea, anyway.